Here is a Fantastic article I found about lighting for when you are just starting out as a photographer or if you have any questions regarding where to start when it comes to buying lights! Enjoy! :)

-Samantha

Beginner's Guide to Lighting Kits

by

Gary Miller, March 2010 (updated February 2011)

One of the goals of working under artificial light is to empower

ourselves to harness our knowledge and creativity to produce

predetermined results. It could be working with one or two small

speedlights or a few inexpensive fluorescents. It could also be lighting

a complex fashion set with thousands of watt-seconds of strobes,

softboxes, reflectors and spots. Once we start to understand that the

beauty of artificial light is that it can be carefully controlled, our

results will soon match our vision. And a lighting setup can be a simple

three light setup or dozens of strobes, with different kinds of light

modifiers. The key is

learning

how to control light—any kind. If some of these terms or concepts are

unknown to you at this point, don’t worry. We’ll soon sort them out.

What Are Your Needs and Budget?

In order to begin using controlled lighting, we have to decide what

kind of lights we need. The number of photographic lighting choices

today is mind-boggling. Tungsten. Small flashes. Big power packs.

Monolights. HMI’s. Fluorescent. The number of offerings is enough to

confuse even the most levelheaded photographer. So how do we make sense

of all this?

The first question you should ask yourself is for what purpose are

you going to use the lights? Still photography only, or video and

stills? Portraits only? Large scenes like the inside of buildings or

factories? Do you want to be completely mobile, away from electrical

power (in which case you will need battery-powered strobes) or is it

okay to be tied to the wall outlets?

If you are going to be doing both video and stills, you will need

some kind of steady lighting. This can be simple tungsten lighting, or

the more modern quartz variety or the latest fluorescent or

LED technology.

Obviously you can’t use flash for video but of course you can use

constant lighting for stills. So the choice is easy and there are lots

of individual lights as well as kits from which to choose.

A portrait setup is much simpler than a setup capable of interiors,

industrial or more advanced needs. With portraits you can get by with

one or two lights if necessary. Three or four are ideal. For interiors

or location work it’s not uncommon for pros to use upwards of a dozen

strobes.

Another consideration is cost. Very few photographers just starting

with artificial light know what the future portends enough to plop down

$10,000 or more for a professional

photo

lighting setup. A lot of this equipment is costly, so thinking ahead

and planning carefully will prevent a lot of grief in the long run.

Ideally, you should be able to add equipment over the coming years and

not render anything useless. To wit, I have Norman 200b portable strobes

that are 25 years old and work as well as they did leaving the factory.

Talk about workhorses!

This guide is for beginners getting started with studio lighting. I

go over various lighting kits on the market for photographers who want

to start experimenting with studio lighting but don’t want to drop a lot

of money on a kit. Future articles will go over more advanced and pro

lighting kits.

On-Camera Flash versus Off-Camera Flash

So let’s take a look at some possible scenarios and then examine the

most popular and well-proven photographic lighting equipment available.

More than likely, you are at the stage where you feel limited by the

camera’s built in flash. When subjects are near the camera, the

background is pitch black. Things that are too close are wildly

overexposed. People’s features, like high cheekbones, seem flat and

lifeless. You wish you could just grab the flash and re-position it.

Well, you have the right idea but, as you know, the only way to do

that is to buy a separate, shoe-mount flash. The ones made by your

camera manufacturer are the best choice, especially when you’re looking

for all the bells and whistles available today like

TTL flash metering, remote power adjusting, extra battery options, etc. Most of them are in the $300-$500 range such as the

Canon Speedlite 580EX II Flash, (

compare prices) (

review), or

Nikon SB-900 AF Speedlight, (

compare prices) (

review). If your budget is tight, however, there are a number of low-cost substitutes that will work just fine. The

Vivitar 285HV Flash, (

compare prices), is an excellent low-cost solution (~$110), for example. So is the

Sunpack PZ42XC Flash, (

compare prices).

Make sure you get a photo “eye” (a remote sync device that triggers the

second or more flashes) or radio sync system. We’ll discuss all this

and more in detail further down in this article.

Video or Stills? Or both?

First question: stills, video or both? If your answer is both (lucky

you, probably the proud owner of one of the new HDSLR’s) you need steady

lighting, often called hot lighting. It’s traditionally been called hot

lighting because the bulbs were, well, hot. Think about a 1,000-watt

tungsten halogen bulb. Or a 2,000-watt floodlight. Even putting your

hand near a 100-watt household bulb gives you an idea of how light

equals heat with conventional tungsten lighting. This is okay if you

have a big, air-conditioned studio in which to work but most of us can’t

afford that luxury. Our studio is often a corner of the dining room or

maybe an extra room off the garage. In a little space, the heat given

off by tungsten light can be unbearable. However, thanks to fluorescent

and

LED technology, lights have been developed that achieve the same level of light output without cooking you and your subjects.

Additionally, today’s DSLR’s are also much better performers with

less light. This means instead of 1,000 watts of light you can do nicely

with 300. It also means you can spend proportionately more money on

accessories like light modifiers, stands, clamps, backgrounds, etc.,

etc

Basic Lighting Kits: Hot Lights

My first choice would be a small lighting kit from

Lowel Light Mfg. They have an extraordinary number of choices, from small camera-mounted

LED

lights to multiple large fluorescents as well as their well-known

tungsten kits. Lowel has always been an innovator in hot lighting, and

now they have continued that tradition in cold lighting as well. Prices

start at $100-$300 for individual lights and $500 and above for complete

kits. A three-light kit is minimum (main light, fill and hair, plus

optional background light) for those interesting in making the

best-looking imagery (or footage). The Lowel Rifa is a great general

purpose light system, and their Tota is probably the best-known

workhorse along with the DP Omni. My favorite is the

Lowel DV Creator 44 Kit, (

compare prices),

which runs about $1100.00 but has everything you need—a very extensive

list of heads, stands, frames, gels, etc. all packed into a handy case.

Other manufacturers with a good reputation for hot lights are Arri, Chimera, Cool-Lux, Dedolight, Elinchrome, Hensel,

JTL, Norman, Interfit, Photoflex, Smith-Victor and Wescott. All are available from our partners. Go

here to search for lighting gear. Many of them offer kits similar to Lowel, with a wide variety of models and power to choose from.

Flashpoint, Adorama’s low-cost proprietary brand, makes an excellent low-cost cool fluorescent light kit:

Flashpoint 3 Light Fluorescent Kit, (

compare prices),

and is available for about $160. It comes complete with light stands,

two kinds of umbrellas (shoot-through and silver reflective), standard

reflector, bulbs and case. This is really a great choice for the

beginner in terms of cost and value.

Smith Victor, a manufacturer known for high-quality but moderately priced gear, offers a great

Smith Victor KSB-1250F Kit, (

compare prices), including both tungsten as well as fluorescent bulbs, light stands, case and an excellent guide to lighting. About $600.

An important note for safety’s sake: Hot lights are,

indeed, hot. Be careful! Don’t let flammable fabrics or other items get

close to the lights. When you use diffusion material makes sure it’s of

sufficient distance from the bulb so there is no smoke or burning

smell. Wear gloves when handling accessories like barn doors than can

get really hot during a shooting session. And always use sand bags or

other weights to securely anchor light stands if there is at all the

possibility of them tipping over.

Usually the heat alone is enough to encourage you to practice safe

handling, but it’s a serious concern, so please take heed. Better safe

than sorry. It’s also an excellent idea to have a fire extinguisher

nearby. In fact, it’s mandatory in a commercial studio so do as the

pros do.

How Many Lights? What Accessories?

Whether it’s constant or strobe lighting, the basic kit should

include one broad source of light, with an umbrella or softbox, a fill

light (can be a shoot-through umbrella), a hair light with snoot or

grid, and a general-purpose light for the background. You can start with

one light (the main) and add to your collection over time as your

budget allows.

The umbrella or soft box spreads the light over a wider source,

giving softer shadows and a “wrap around” effect that is flattering and

very elegant looking. The fill light can be used with another umbrella

or can simply be reflected off a simple piece of white Foamcore™ at a

45-degree angle to the subject. The hair light and background light can

be smaller units; the only requirement is that the hair light should

have a snoot (cone that keeps stray light from hitting other areas) or

grid (waffle-like device that does the same thing). The background light

might have a filter frame so you can experiment with different colored

filters or gels.

Remember that tungsten light, typically quartz, is 3200 degrees

Kelvin. So if you are shooting a scene with daylight pouring in a

window, you either have to cover the window with an orange gel, called a

CTO, or cover the lights with a blue gel, called

CTB.

Which solution you use is usually a factor of which light is stronger. A

large living room with half a dozen light fixtures is easier to match

by gelling the window, for example. A good source for a lot of hot light

accessories is

The SetShop or

MarkerTek).

Before leaving hot lights, we should note that there are two really

inexpensive solutions to hot lights. One is at your local hardware

store: aluminum reflectors with a 500-watt household tungsten bulb, $15

to $20. The other is through dealers like Adorama that now offer

inexpensive fluorescent lighting fixtures and kits with the Flashpoint

brand, starting at $35 for one light to $100 for a fixture that holds

four bulbs. Cool! (Literally.)

So our beginner’s tungsten or fluorescent lighting kit consists of:

Small Speedlight Set

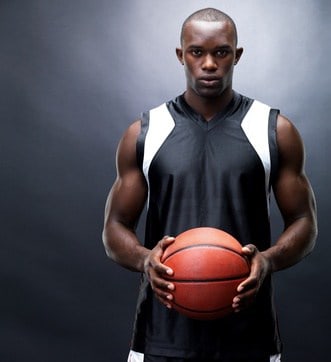

If you are only shooting stills, you can build your electronic flash

system the same way. Start with one small extra speedlight, get some

experience with it, then add a larger umbrella or softbox unit. Then add

another small speedlight with grid for the hair light and finally a

fourth light for background. You may find that you don’t need the hair

and background lights for your particular style of photography. The

four-light system is the traditional setup for studio or executive

portraits, but you may find your interest lies in shooting babies or

little children, where a two-light umbrella or softbox setup is enough.

A good small speedlight set includes:

Note: Instead of umbrellas you can use some of the products that HonlPhoto

offers. They have an amazing number of innovative small speedlight

accessories that are inexpensive and very effective, such as small

reflectors, gobos (to shield the light), filters and grids (to focus the

light).

Monolights & Monolight Kits

Up one step from the shoe-mounted flash is a monolight, sometimes

called a monobloc. This is a small AC-powered strobe that is completely

self-contained. Reflector, power supply, umbrella and light stand holder

and AC power cord are all built into one unit. They range in size from

the proverbial loaf of bread to ones that are about the size of a

toaster oven. The advantages are (in most cases): built-in modeling

light, no need for a separate power generator, built-in photo eye or in

some cases radio sync slave, adjustable power output, and ease of using

light modifiers like umbrellas. They also provide some degree of

redundancy for backup, that is if you have three or four of them and one

fails, you’re usually not completely out of luck. If you’re using a

generator-based system and the unit goes south, you need to have at

least one for backup or be able to rent one nearby.

One of my favorites in the monobloc category is the compact

Bowens Gemini 200 Kit, (

compare prices).

These are very well-made, reasonably priced ($375.00) professional

quality units that have withstood the test of time over the years.

Today, they can also be powered by a battery unit (such as the

Bowens BW7693 Small Lightweight Travel Pack Starter Kit, (

compare prices)

(about $600) which is essential for location solution. For the budding

photographer who will eventually add to his or her kit when moving up,

these are an excellent investment.

Wescott offers a value-driven three monolight setup:

Westcott Strobelite Three Monolight Kit, (

compare prices),

including three 150 watt-second monolights, stands, umbrellas, sync

cord and floor positioning mat (a great learning tool) plus a complete

lighting course on

DVD

So, here’s our monolight kit:

- 3 monolights, at least 150 watt-seconds each

- 3 light stands

- 2 smalll clamps

- 1 roll Gaffers tape

- 1 barn door

- 1 reflector

- 1 snoot

- Extension cords (hardware store

The other alternative for low-cost beginner outfits is used equipment. If you check the

classified section of Photo.net,

you will often see an old Norman 200b or Bowens monolite or similar

strobes for a very reasonable price. If they have been used continuously

or at least from time to time, you’re more assured of getting a working

unit. Older units that have been sitting around for many years often

have dried up capacitors. Still, if the price is right, having them

repaired can be a relatively inexpensive investment.

Radio Slaves

We mentioned the challenge of synchronizing all your lights. That is,

they all have to go off at the same time. There are four ways of doing

this. First is hard wiring, that is, all the flash units are plugged

together by sync cords and extensions. This is the least desirable

because it is prone to failure due to broken wires or other seemingly

invisible factors. Even a slight bit of humidity and one or more of the

strobes will undoubtedly fail to fire—and that will be the best

expression on your subject’s face, of course. You also have the problem

of running cables around doors and walls. So let’s look at the other,

wireless, options.

The least expensive way is with small light-sensitive triggers that plug into the sync cord connection of your speedlight.

Wein

was a pioneer in this field and continue to dominate it with new and

improved products every day. They range in price from $15 for the basic

100-foot range model to $100 for a super-sensitive 1000-foot model.

There are a number of other manufacturers making light-sensitive

triggers, including Adorama, Morris, Metz, Nikon, Norman, Photogenic,

Sunpack and Speedotron. All work pretty well indoors, but outdoors in

bright sunlight is another matter. Some of them will tolerate a certain

amount of sunlight; others will not tolerate any at all.

The same problem is with infrared triggers. They work fine as long as

you have indoor line-of-sight conditions but outdoors they can be

problematic. The most popular and reliable device is the radio slave.

These range in price from very cheap ones you find on eBay to the

professional’s favorite—the PocketWizard. In addition to triggering the

strobes, PW’s can trigger the camera as well. At the Kentucky Derby or

Olympics it’s not uncommon to see 20 or 30 cameras set up for remote

firing, all dressed up with PocketWizards.

A couple of companies—PocketWizard, Radiopopper, Cactus, Quantum—are now making radio slaves that work in the

TTL mode. That is, you set your camera and strobe to

TTL (through-the-lens) and the flash units puts out only enough light based on what you have set the camera’s

ISO. As an example, I took my Canon

DSLR out in the sunlight, put two Canon 430EX II’s on light stands, put a

PocketWizard MiniTT1 Transmitter [Canon], (

compare prices) on the camera and a

Pocket Wizard FlexTT5 Transceiver [Canon], (

compare prices)

on each strobe, and started shooting. Perfectly exposed images right

off the bat! Totally amazing, foolproof and flexible. You can also shoot

in what’s called the high-speed sync mode, enabling f/2.8 shots

outdoors in bright sunlight to put the background beautifully out of

focus. What’s nice about the PocketWizard system is that any upgrades

are easily incorporated via downloaded firmware.

Conclusion

There are lights and kits for every budget and purpose. Don’t let the

myth that lighting is expensive keep you from enjoying this critical

aspect of photography. Start small and expand as you get the feel of it.

However you acquire your lights, the most important advice is to use

them. Practice setting up one, two or more lights. Bounce them off

umbrellas, foam core reflector boards, or the walls and ceilings.

Practice using hair and background lights, or mixing artificial light

with daylight. You’ll soon find that even the simplest lighting setups

can produce dramatic images.

Look at photographs made with artificial light and analyze how they

were lit. What are the qualities of the light (soft, hard, edge, etc.)?

How does the lighting convey the mood and intent of the photograph? In a

portrait, what does lighting contribute to the viewer’s perception of

the subject?

Don’t just put up your lights one way and then after your session take them down and put them away. Experiment. Use a slow

shutter speed

to let the background burn in. Use motion to add intrigue. Put the

lights up high, down low, to the right and to the left. The only way you

will maximize your investment in lighting gear is to practice using it.

About the Author

Gary Miller has been

photographing, writing, and editing for magazines, corporations and

organizations for more than 25 years. He has also written, produced and

directed hundreds of corporate and

educational

films and videos. He counsels corporations, organizations and

individuals on public relations and marketing strategies, including web,

print and photography. Today he is an active freelance writer and

photographer on subjects including photography, sailing, fishing, travel

and video production. His editorial work appears in

TV Guide,

Time,

Newsweek,

Yachting,

Business Week,

Motor Boating & Sailing,

Good Old Boat,

Soundings,

National Wildlife

and others. Some of Gary’s film and video clients include Financial

Management Network, Salomon Smith Barney, Stauffer Chemical,

MAC Group, MasterCard International and

AMEX. He is the author of a book on

Freelance Photography (Petersen Publishing), and guest lecturer/workshop host at the New School, New York City.

http://photo.net/learn/lighting/guide-to-lighting-kits/beginner/